Superchargers and turbos are nothing new for cars, but there’s a surprisingly long history of motorcycles harnessing mechanical steroids. Other than Kawasaki’s latest H2 line and aftermarket shenanigans (think turbo Hayabusa), most people don’t think about forced induction in motorcycles. Bikes in the 1920s, however, were already using superchargers and chasing land speed records. I have a 2021 Kawasaki ZH2, the hyper naked variant of the H2 series, and the supercharged 998cc inline-four is pure insanity at around 200hp and over 100 lb-ft of torque. For perspective, my previous Honda cb1000r was already FAST at 143hp and 77 lb-ft of torque with a naturally aspirated 998cc counterpart. Superchargers are no gimmick.

Daredevils of Europe

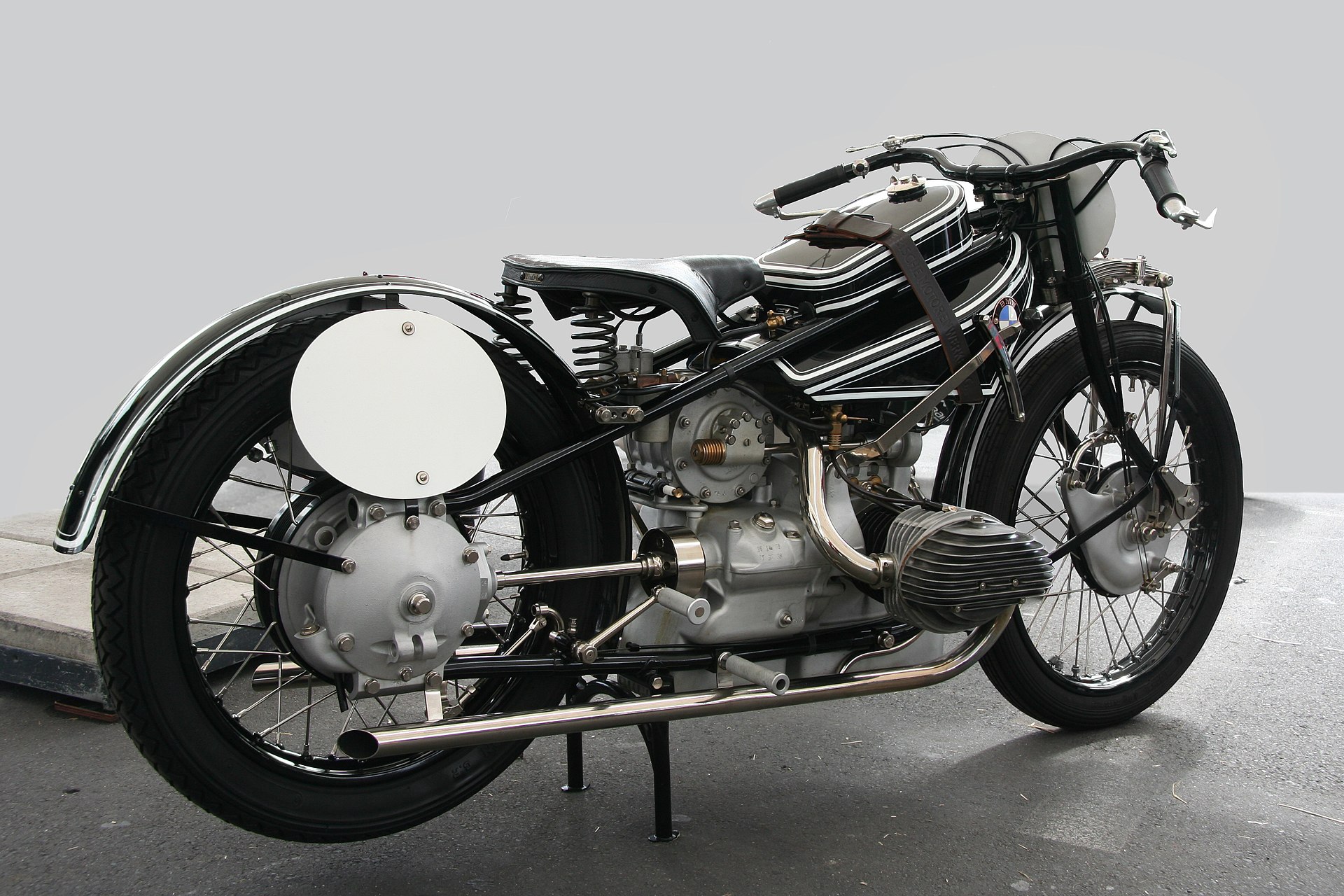

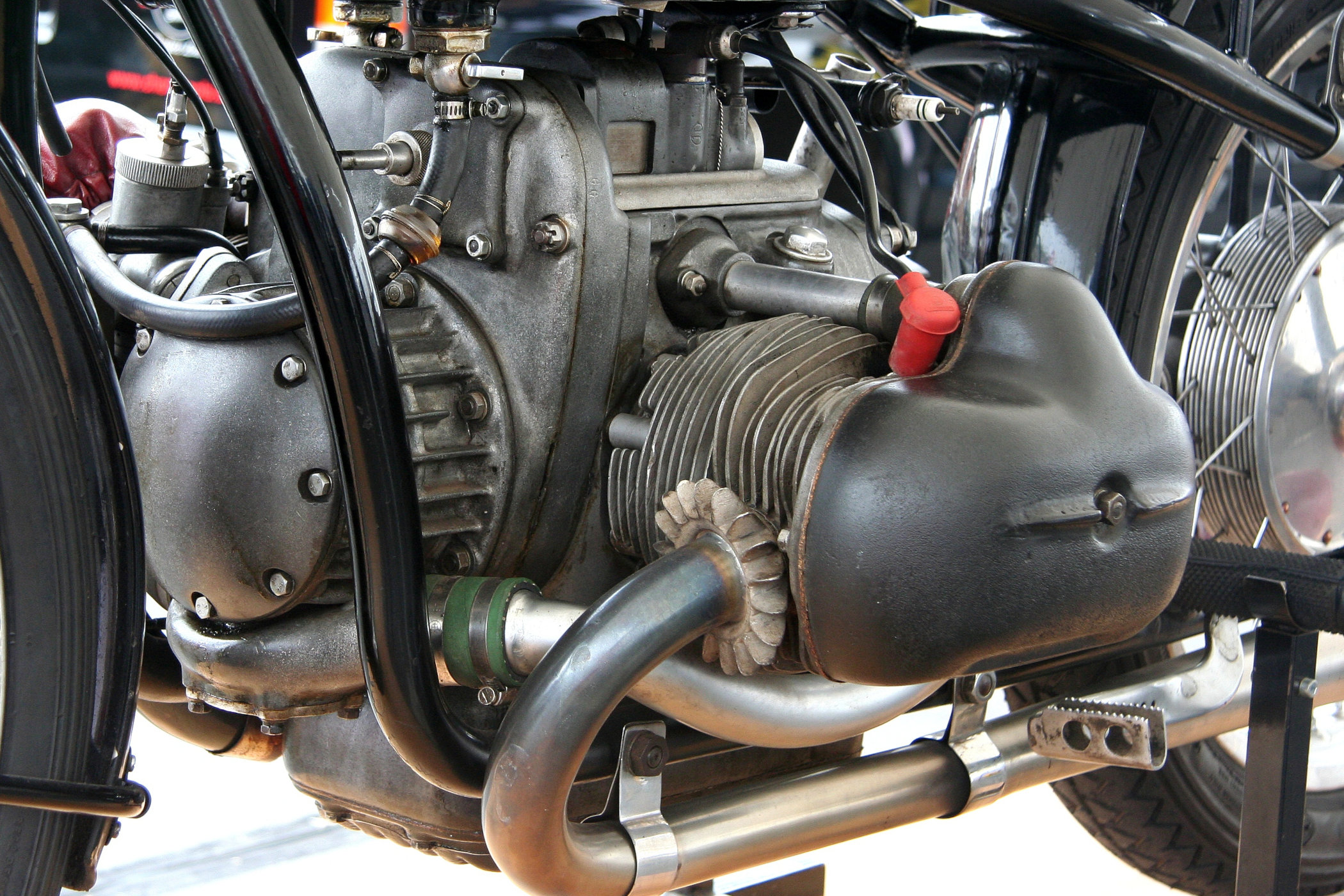

In the 1920s and particularly the 1930s, superchargers were all the rage in European racing. BMW was one of the early innovators with the WR 750 in 1929, which is impressive considering they only jumped into the motorcycle game in 1923. It had an overhead-valve, four-stroke 750cc supercharged boxer engine (horizontally opposed cylinders) that German racing champion Ernst Henne took to 134mph for a land speed record. That’s fast for a bike, even for many street riders today, and this was on a prewar chassis and tires. No thanks.

English racers were dominating the track in the 1930s and the WR 750 was falling behind, so BMW introduced the Type 255 Kompressor with a Swiss-made Zoller supercharger pushing a 500cc boxer engine to 60hp. That might sound a bit pedestrian, but it was a bona fide superbike at the time. It won the Senior Tourist Trophy race in 1939 at the Isle of Man, marking the first time an English racer lost since 1907. Georg Meier was at the controls and won the Belgian motorcycle Grand Prix the same year, becoming the first racer to exceed 100mph on a competition lap. Most European racing teams had embraced superchargers in the mid-1930s, which were often doubling the power output of prewar engines.

Inevitable Deaths

Prewar Supercharged bikes were being designed with aerodynamics in mind, particularly for speed records, directly linking them to modern sportbikes. With so much power and innovation, it was inevitable that a need for speed became an addiction. In 1937, Eric Fernihough took his supercharged 1,000cc Brough Superior to 169.79mph, which is mind-boggling for that era. He died the next year chasing another record. Brough Superior was the ultimate “Rolls Royce” of motorcycles and very exclusive, and the most famous rider to die on one was T. E. Lawrence (aka Lawrence of Arabia), albeit on a naturally aspirated SS100 model in 1935. Unfortunately, it wasn’t uncommon for both racers and speed demons to die at the hands of their supercharged two-wheelers, so the Fédération Internationale de Motocyclisme (FIM) banned forced induction in 1946 when racing resumed after the war.

Prior to the ban, there were some seriously radical bikes. British manufacturer AJS (A. J. Stevens & Co.) produced a massive supercharged V-4 that proved unreliable in races but consistently hit very high speeds. BMW, Moto Guzzi, DKW, Gilera and more were the dominant supercharged teams with winning records and rockets on wheels, using boxer, V-twin and single-cylinder engines in either two or four-stroke configurations on the track. Speeds in excess of 150mph were a reality when Ford’s Model A topped out at 65mph. It was the golden age of forced induction and it wasn’t until the late 1970s that we’d see a (short-lived) return.

What is Forced Induction?

Superchargers and turbos do the same thing, just in a different way – forcing pressurized oxygen into the engine for increased power. Think of it as fanning the flames. Both use impellers that spin at very high speeds to compress the air, 50,000rpms or more, but a supercharger is powered directly by the engine. A gear train is used in modern motorcycles to spin a centrifugal supercharger, while cars typically use a belt that wraps around a pully between the engine and compressor. The advantage of a supercharger is that it’s always pushing air into the cylinders with no hesitation as the engine keeps it spinning, but it’s also robbing the engine of a bit of power in the process. Of course, the added boost more than makes up for that.

A turbo compresses air via two impellers, one that spins from exhaust gases and a second connected one that feeds the engine. Instead of the engine directly powering a turbo, exhaust from the header pipes does it like a windmill connected to the compressing impeller. This has an advantage as exhaust gases are “free energy” that’s not being taken from the engine itself. However, it can take time for the exhaust to push enough air through the impeller to really get it spinning, creating a hesitation known as turbo lag. Step on the gas and it can take a second or two for the boost to kick in. Although modern turbos have mostly solved turbo lag, it does persist to varying degrees.

Turbo’s Time to Shine

In the late 1970s, forced induction returned to factory motorcycles, but this time in the form of turbos. It was a time of ambitious dreams by Japanese motorcycle manufacturers with the big four jumping in headfirst – Kawasaki, Honda, Suzuki and Yamaha. In 1962, the Chevrolet Corvair Monza and Oldsmobile Jetfire became the first production turbocharged cars, but it wasn’t until the 1980s that turbos really took off. The trend was the result of a boom of compact cars with small, fuel-efficient engines that lacked the romance and thrill of gas-guzzling muscle cars (mainly in the US), a byproduct of the 1970s oil crisis and rising air pollution.

Japanese Hooliganism

Kawasaki wanted in on the fun and launched the 1,000cc Z1R-TC in 1978, which was a modified Z1R with a factory-authorized Rajay turbocharger fitted. The result was a 130hp superbike that was so radical, buyers had to forfeit the factory warranty. That’s a bold request for a bike selling at authorized dealerships and it took a special kind of buyer. It was limited to only 250 units as production was complex and expensive, but I would’ve been first in line for such a nonsensical thrill. Honda’s attempt was less successful with the 1982 turbocharged CX500 which suffered from horrible turbo lag, so the bigger CX650 replaced it in 1983. The jump to a 650cc engine and tweaked turbo resulted in a fast 100hp bike, but persistent turbo lag and high prices doomed the effort and both were discontinued by the end of 1983. Yamaha and Suzuki were also players with the 1982 Yamaha XJ650 Turbo and 1983 Suzuki XN85, and Suzuki’s bike was the best of the bunch (thus far). It only pushed out 85hp, but was considered very fast at the time and had a purpose-built chassis for the increased power. Turbo lag was also reasonable and the XN85 remained in production for five years, longer than any of the other Japanese turbos.

Kawasaki’s Rise to Power

Although Suzuki’s attempt was the most commercially successful of the short-lived Japanese turbo era, Kawasaki delivered a second turbocharged bike in 1984, the GPz750 Turbo. This was the most polished and capable of them all. It pushed 112hp from a 738cc engine and was faster than the brand’s huge GPz1100, a top-of-the-line naturally aspirated sportbike. In fact, it was the first middleweight motorcycle to truly challenge the heavyweights and proved that forced induction was much more than a curiosity. Tragically, it was still too complex and expensive, resulting in maintenance issues and prices that neither the manufacturer nor customers could embrace. Naturally aspirated counterparts were also hitting their stride in the 1980s with incredible speed and performance, so the ambitious turbocharged concept joined spandex and mullets with an untimely death.

Fast forward to 2014 and Kawasaki was back with a vengeance. The new Ninja H2 was the first factory-supercharged motorcycle since World War II and used an in-house, centrifugal supercharger that didn’t require a separate intercooler. It boosted a 998cc inline-four to 228hp and 104.9 lb-ft of torque, while the track-only Ninja H2R had 326hp and 121.7 lb-ft of torque, making it the fastest production motorcycle of all time. I’m not sure what sorcery was harnessed within Kawasaki’s walls, but this ground-up supercharger was brilliantly executed, resulting in some of the most thrilling, torque-blasting rides of the 21st century.

My ZH2 is a more street-oriented variant with the second generation 998cc supercharged powerhouse, producing a (relatively) more manageable 197hp and 101 lb-ft of torque. It still has more power than I’ll ever fully exploit and will launch to mars if pushed too hard, and it’s by far the fastest bike I’ve owned. The supercharger also produces a chirping sound on deceleration, supposedly due to the impeller breaking the sound barrier, so I’m always reminded that I’m riding something special.

Ludicrous Speed

It’ll be interesting to see if other manufacturers jump on the latest forced induction bandwagon that’s wholly dominated by Kawasaki. Comparable bikes like Ducati’s V4 Streetfighter and many others have similar power specs without superchargers or turbos, so it’s arguable that forced induction is obsolete in the motorcycle space (notwithstanding the aftermarket madness). The supercharger’s low-end torque is more thrilling than naturally aspirated superbikes that need to be revved higher to find the power band. Kawasaki’s H2 line will take you to ludicrous speed when lightspeed is just too slow.

https://monochrome-watches.com/the-petrolhead-corner-the-long-and-short-history-of-superchagerd-turbocharged-motorcycles/